I had butterflies in my stomach.

He’s always had a nervous stomach.

She was sick with worry.

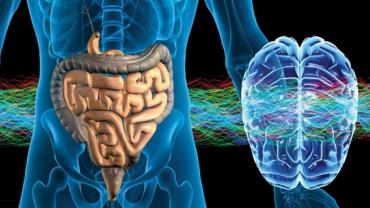

The English language is full of phrases that suggest a connection between the head and the stomach—or more precisely between the brain and the gastrointestinal tract. And certainly it doesn’t require a medical degree to understand that there does seem to be a link between what goes on in our head and what goes in our gut and vice-versa. When we’re nervous scared worried or otherwise upset we tend to lose our appetite and may even feel a little nauseated. Abject terror—such as some people experience before speaking in public—can even cause a sudden and urgent need to…shall we say visit the bathroom? So if these feelings are all in our heads then why do our intestines seem to bear the brunt?

Clearly things are not “all in our heads.” The two-way communication between the brain and the gut is important and influential enough that Michael Gershon M.D. who pioneered much of the early research on this topic wrote a medical professional and layperson-friendly book with the not-so-subtle title The Second Brain: A Groundbreaking New Understanding of Nervous Disorders of the Stomach and Intestine. Second brain indeed. No wonder we feel a sinking feeling in the pit of our stomach when we receive bad news.

The connections between the gut and the brain are receiving increased attention due to the new research focus on the influence of the intestinal microbiome on psychology including conditions such as anxiety and depression. This “gut-brain axis” is a big piece of the puzzle. Scientific papers as well as books for the mainstream press have catapulted these issues to the forefront. Still the microbiome is only one way by which what goes on in the gut may affect what goes on in the brain—or to paraphrase the Las Vegas tourism commercial “What happens in the gut does not stay in the gut.”

The second brain is also called the enteric nervous system. The nerves that innervate the intestines are a brain unto themselves capable of acting independently of the “other” brain. But to complicate matters obviously the enteric nervous system can and does send and receive feedback to and from the brain in our skulls. It is quite possible that patients who complain of anxiety depression or other disturbed mood states but who seem to have no identifiable life circumstance triggers (financial worries death of a loved one career troubles etc.) may be experiencing psychological effects of problems in the gut. This could be anything from microbial imbalances to increased small intestinal permeability (a.k.a. “leaky gut”) to regular ingestion of foods they may not realize they’re sensitive to be that gluten dairy nightshades salicylates FODMAPs etc.

On the flipside individuals with healthy diets and lifestyles who experience unexplained diarrhea constipation or other types of bowel distress may be reacting to situations and events in their lives that have nothing to do with what they eat. The difficult part of course is determining which of the “two brains” is wreaking havoc on the other. A good clinician will work with a patient to identify which is the more likely answer and help them remedy the issue.

Hippocrates famously said that all disease begins in the gut. In more modern times the connection between disturbed intestinal function and altered psychology has been leading people to try and help themselves since at least the early 1900s when Sidney Haas M.D. developed the Specific Carbohydrate Diet. This was an elimination diet originally intended to help those with celiac disease and more recently it has been used to improve other intestinal maladies such as Crohn’s disease ulcerative colitis and diverticulitis. (This program experienced a resurgence in popularity after being reintroduced to the public through the book Breaking the Vicious Cycle.) Another nutritional strategy intended to help individuals with compromised intestinal function and psychological disorders is the Gut and Psychology Syndrome (GAPS) diet. There are numerous anecdotal reports of children on the autism spectrum improving by following diets designed to repair intestinal permeability. Indeed “gastrointestinal symptoms are a common comorbidity in patients with autism spectrum disorders” and there may be an important role here for special diets and other interventions such as probiotics that may favorably alter the gut-brain axis.

Apart from the role of a leaky gut alterations in serotonin signaling affect gastrointestinal motility. It has long been known that there may be a connection between low serotonin or malfunctioning serotonin receptors and depression so it should not be surprising that depression and constipation are common comorbidities. However the serotonin theory of depression is being called into question by some researchers. Altered serotonin signaling may play an even larger role in the gut than it does in the brain.

Though much research has been done much more remains. There are far more questions than answers but patients may take comfort in knowing unpleasant feelings they experience in their minds are not really in their head at all but come primarily from their gut. Identifying offending foods and repairing a leaky gut takes time but this also allows patients to take control of their health rather than remaining passive victims feeling helpless in the face of unexplained dark moods and anxious thoughts.