The composition of the human microbiome shifts during the aging process. Profiles of the gut microbiome in older adults indicate decreased levels of biota from the phylum Firmicutes and higher levels of Bacteroidesspp. Reduced levels of bacteria that produce butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA), have also been found in elderly individuals. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are produced by bacteria from dietary fiber in the gut microbiome. These age-related shifts in gut microbiota may be due to dietary changes, decreased mobility, increased medication, other lifestyle changes, or physiologic changes in stomach acidity and other aspects of digestion.

Changes in mood, other aspects of neurological health, and inflammation have been shown to influence the health of the gut microbiome. The composition of the human microbiome has been linked to diet. A recent study published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences explored the relationship between gut microbiome dysbiosis, inflammation, and dietary intake of tryptophan in aged mice. Tryptophan is one of nine amino acids that are considered essential, which indicates they are not synthesized by humans and can only be obtained from supplementation or diet. Tryptophan is important in neuropsychiatric health, gut health, and the immune system. Metabolites of tryptophan support gut health and overall health, such as indole-3-propionic acid, which plays an important role as an antioxidant in neuroprotection. Deficiencies in tryptophan have been associated with major depressive illnesses and a systemic proinflammatory state.

The research study measured certain proinflammatory cytokines and gastrointestinal taxonomy in the exploration of the change that occurs when tryptophan levels are altered in the diets of aged mice. The study showed elevations in interleukin (IL)-17a, IL-1a, and significant elevations in IL-6 in tryptophan-deficient diets. It was determined overall that the tryptophan-deficient diet had elevated proinflammatory cytokine levels as compared with those fed normal or tryptophan-rich diets.

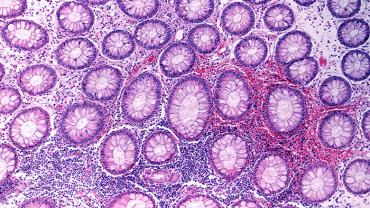

The authors reported that changes in the abundance of many microbial bacteria occurred in the presence of tryptophan-deficient diets. The study found significant increases in Enterorhabdus in tryptophan-deficient mice. Species in the Enterorhabdus genus have been associated with murine ileocecal mucosal inflammation, and some Enterorhabdus species have been isolated in mice with intestinal inflammation and colitis. The researchers also reported increases in microbes from the genus Adlercreutzia and Acetatifactor in tryptophan-deficient mice. Acetatifactor muris has been associated with gastrointestinal inflammation. Decreases in microbes from the Lachnospiraceae family were also observed in tryptophan-deficient conditions. Species from the Lachnospiraceae family produce butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids. Decreases in Clostridium species also occurred in the tryptophan-deficient environment, which may be associated with lower levels of serotonin synthesis in the gut microbiome. Decreases occurred in Oscillibacter valericigenes, a species whose deficiencies have been linked to Crohn’s disease and inflammation. Blautia species have been associated with anti-inflammatory properties. Blautia populations were also decreased in mice fed a tryptophan-deficient diet.

Physiological and lifestyle changes occur during the aging process, and the gut microbiome also experiences changes. The results from this study suggest that ensuring adequate intake of tryptophan via supplementation and/or the diet may support the body’s gut microbiome, gastrointestinal health, and a normal response to inflammation.

By Colleen Ambrose, ND, MAT