There are many phrases that describe the nutritional state of millions of people in the modern industrialized world: “Overfed but undernourished.” “Starving in the land of plenty.” Sayings like these describe the phenomenon in which while it appears from the outside that obese people have a surplus of fuel stored on their bodies inside at the cellular level they’re actually starving. They may have a surplus of energy in the form of stored adipose tissue but they are deficient in micronutrients.

Nutrient deficiencies are a common long-term side effect of obesity surgery particularly the procedures that alter the digestive tract resulting in compromised capacity to break down foods and assimilate nutrients. Researchers from Johns Hopkins University have revealed that nutrient deficiencies are also common prior to bariatric surgery. Detecting and correcting these deficiencies as part of the pre-operative strategy may help patients fare better during recovery and beyond.

Even though nutrient deficiencies are a well-recognized effect of many types of bariatric surgery many patients receive little to no assessment of their nutritional status before undergoing a procedure. According to an analysis that covered studies involving over 21000 patients undergoing some form of bariatric surgery only 21% were tested pre-operatively for levels of vitamin B12 which is one of the known likely deficiencies resulting from gastric bypass procedures. Rates of pre-surgical evaluation for other nutrients were 17% for folate 7% for vitamin D and 21% for iron.

Among the patients analyzed by the Johns Hopkins researchers one in five had deficiencies in three or more of the nutrients assessed: vitamins A B12 D and E as well as iron folate and thiamine. The most common deficiencies were in iron (36% of patients) and vitamin D (71%). The shortfall in iron is striking since just 2% of men and 9% of women in the general U.S. population are iron deficient. The low vitamin D levels are less surprising considering that over 40% of the U.S. population is estimated to have inadequate vitamin D levels. Moreover obese individuals tend to have lower serum levels of 25-OH vitamin D due the body sequestering vitamin D in the adipose tissue leaving less available from cutaneous conversion. Even after whole-body irradiation obese study subjects have 57% lower serum vitamin D levels than non-obese subjects. After supplementation with 50000 IU of vitamin D2 blood levels of D in obese subjects did not increase as much as those of non-obese subjects.

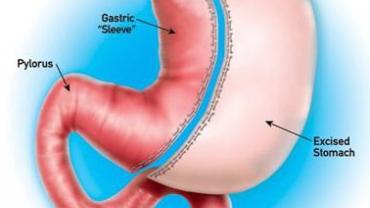

Patients undergoing procedures that alter the structure and physiology of the GI tract such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) biliopancreatic diversion and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch were more likely to have been evaluated for nutritional status prior to surgery than were patients undergoing procedures that reduce the size of the stomach in order to limit food intake such as gastric banding and vertical banded gastroplasty. This may be because restrictive surgeries are perceived as being less likely to induce nutritional deficiencies since they do not alter the absorptive capacity of the intestines. Patients who undergo restrictive surgeries do tend to fare better in the first twelve months after surgery but beyond that timeframe their micronutrient status is not significantly different from that of individuals who opted for RYGB. They are equally compromised nutritionally speaking.

Considering that candidates for bariatric surgery were likely following relatively poor diets to begin with or had hormonal and/or environmental obstacles getting in the way of optimal nutrition odds are that bariatric patients do have multiple nutrient insufficiencies if not overt deficiencies. Regardless of the type of surgical intervention they may choose to undergo correcting nutritional imbalances prior to a bariatric procedure may facilitate a smoother recovery and help patients start their weight loss journey already in a better state of health than they were before surgery.